EVANGILE SELON SAINT MARC, XVI th century

Fragment de manuscrit. Papier. XVIe siècle

EVANGILE SELON SAINT MARC, XVI th century

Fragment de manuscrit. Papier. XVIe siècle

Folio recto verso, portant des traces de réglure à la pointe sèche coté recto.

Cette page concerne le début du texte de l’Evangile selon Saint Marc, généralement précédé du portrait de l’Evangéliste.

Le premier verset comporte cinq lignes.

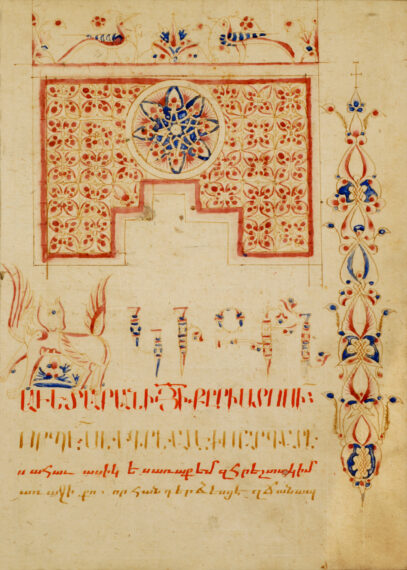

La première ligne débute par une lettre en forme de Lion ailé, symbole de Saint Marc, suivie de majuscules ornementées.

La deuxième et la troisième sont en majuscules erkat’agir, écrites à l’encre rouge puis jaune.

Les mêmes couleurs dans le même ordre se répètent pour les quatrième et cinquième lignes mais écrites en minuscules bolorgir.

La suite du texte, qui va jusqu’au verset 9 du chapitre, se poursuit au verso sur deux colonnes de 22 lignes en bolorgir à l’encre noire et comporte des signes de ponctuation et d’intonation. La surface écrite y est de 140mm x 200mm.

Cette première page de texte montre les éléments habituels que l’on retrouve au début des textes évangéliques. Ici, dans des tons de bleu, rouge et jaune, deux oiseaux affrontés surplombent le portique orné en son centre d’une rosace à huit branches et semé de motifs floraux réguliers, s’ouvrant sur un arc trilobé géometrique.

Dans la marge, sur toute la hauteur de la page, court un motif à base de bleu et de rouge terminé par une fine croix à son sommet.

Le texte commence par le mot “Skizbn” (Le commencement), le lion figure la première lettre “S”.

Le texte se lit : Skizbn/avétara ni y[isous]i k'[ristos]i orpês èv grial ê….”Le commencement de l’Evangile de Jésus-Christ comme l’a écrit…”.

L’ensemble de ce décor, la stylisation sobre des formes et la précision du trait, apparentent ce fragment aux manuscrits du Vaspourakan des XVe et XVIe siècles.

La collection du musée possède un autre fragment du même manuscrit représentant un cadre de Table de canons inachevée, à la décoration très schématisée et simplifiée, incomplète de l’ordre des versets.

Edda Vardanyan

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.