LETTER OF THE PRELATE OF ISFAHAN

Manuscript on paper 1744, Isfahan.

LETTER OF THE PRELATE OF ISFAHAN

Manuscript on paper 1744, Isfahan.

This is a beautiful and long missive from Astvatzatour, prelate of the Amènap’rkitch monastery (“of the Holy Savior of All”) in Isfahan, to all the Armenians in India.

Since the sixteenth century, Armenian merchants from New Djulfa in Isfahan, Persia, founded colonies in India before expanding to China.

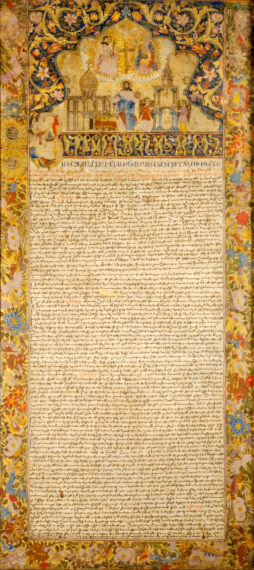

The Trinity is depicted at the top, below which is the Amenap’rkitch Cathedral of New Julfa on the left and its bell tower guarded by two angels on the right. In the center is the apostle Thaddeus, whose relics are in the cathedral, as well as the dexter of Joseph of Arimathea, which can be seen in front of him.

The first line is in ornithomorphic letters, with a beautiful initial: Yerrordak[a]n a[stoua]tzout’i[a]n (“To the triune deity”), it continues on the second in blue erkat’agir: miapétakan ichkhanout’è[a]ns zougahavasar têrout’iann (“[whose constituents] have equal power”). The next line, in red bolorgir, begins with: Anspar hèghmounk’chnorhats, [“Inexhaustible streams of graces”]. From the fifth line onwards, the text changes to black notrgir, except for the word Amènap’rkitch, which stands out each time in red. The whole text consists of endless blessings.

From the middle of the eighth line, one reads: i véray arhasarak hamataratz aménits hayazoun k’ristonéitsd hndk[a]tsv[o]ts*i (“”On all the Christian Armenians spread in the country of the Indians””), the last sign being an ideogram meaning “”country””. Further on we read the name of the prelate, vardapèt Astvatzatour, who succeeds vardapèt Yakob. The recipients of the letter are specified from the middle of the 15th line: haykatohm hamaynits joghovrdakanats ork’i tann bolor hndkats k’aghak’ats èv i gavarats /Aysink’n i madrasou hrtchakéli k’aghak i èv i bankalou baréli k’aghak’i/ èv i p’êkouay pantzalvoy k’aghak’i (“”to all the Armenian communities that are in the cities and provinces of India i.e. that is, to the beautiful city of Madras and to the benevolent city of Bengal and the glorious city of Pegou””).

The penultimate line ends with Amèn. The last is the colophon, which ends with: end hovanial s[r]b[o]y Amènap’rkitch vanis t’iv p’ok’r a dama p[a]tkèr ôr Avétits s[r]b[o]y a[stou]tzatzn[o]yn : Avetis èritsou (“”under the protection of this monastery Saint Savior of All, in the year 128 of the little era, on the 18th of dama, day of the Annunciation of the Holy Mother of God. From the priest Avétis””). The “”little era”” is that of the calendar of Azariah Jughayetsi which begins in 1616, the year 128 being therefore 1744; dama is the name of the month whose 18th coincides with the 7th of April, day of the Annunciation.

Edda Vardanian. Gévorg Ter-Vardanyan. Jean-Pierre Mahé.

La Vieille Charité – Marseille. Exhibition Arménie, La Magie de l’Ecrit- Claude Mutafian, catalog page 373 n°5.77

Editions Somogy 2007

In Armenia, the art of books is linked to the invention of writing. Until the 5th century AD, the inhabitants of the Armenian plateau had successively used the cuneiform script (Urartu), and later, with the various conquests, Aramaic (the Persian period), Greek (the Hellenistic and Parthian period) and Latin characters (under Roman domination).

Driven by the need to have a specific writing adapted to the language, around the year 405, an Armenian monk, Mesrop Mashtots, invented an alphabet composed of thirty-six letters or graphemes corresponding to the thirty-six phonemes of the oral language used in the 5th century.

The most widely distributed and recognized book in this Christian nation was the first to be transcribed: The Bible.

This allowed the many copyists in monasteries to learn the alphabet, and they acted as network for disseminating Christianity, and thereby strengthening Armenian identity. This transmission of a culture and a religion made it possible for the identity of a civilisation remain intact despite the vicissitudes of history.

The texts were at first, for the most part, religious, biblical (The Bible—Gospels) or liturgical (Lectionaries—Hymnaries—Psalms—Homiliaries, etc.).

From the end of the 9th century, there was an increase in the amount of manuscript works produced, propagating the faith of a people through this fundamental medium which is writing: it is the union of the written word and religion that allowed this people to survive, despite the lack of an organised state.

To embellish the written word, painters assisted the scribes, and it is in books that we find the best expression of Armenian pictorial art.

The Armenian book was printed in 1511, but manuscripts had such a predominant role that, unlike other countries, book printing in Armenia did not fully develop until the 18th century and it was not until the 19th century that it reached the stage where it could actually replace the work performed by hand.

In the 10th century, but especially in the early 13th century, a capital letter would be accompanied by a lower case or bolorgir, which was easier to write and took up less space. Paper became available alongside parchment from the end of the 10th century. It was at this time that the Bible began to be copied into a single compilation. This script was used until the 16th century, and continued to exist until the 19th century. The erkatagir, the first form of writing in the 5th century, was then used as the capital letter for the bolorgir, which remained the main script.